the real meaning of photographing my children.” “I lay there certain that his life was ebbing from his unconscious form and thought about.

It takes 11 minutes before medical help arrives, an interval that Mann recalls in a letter to a friend, reflecting on her inability to “even hold a camera up” though she’d exhorted her students to photograph the great events of their lives. It begins with a horrific accident: Mann’s 7-year-old son is struck by a car while she watches helplessly from across the road.

By the time Sally and Larry arrived, both corpses had been removed, but the authorities left behind a load of forensic evidence: enough prescription pills (mostly painkillers) to fill the huge cardboard box in which a washing machine had recently arrived.įurther along in the book is a sequence I’ve reread several times without fully understanding it, and without being able even to form an opinion. She reloaded, put the gun barrel in her mouth and shot herself. In July 1977, Larry’s mother arose, loaded a shotgun and shot her husband in the head. Lots of people have bad-in-law stories, but this young couple’s takes a turn. Realizing that their son’s fiancée was unlikely to speed their upward mobility, the Manns tried to sabotage the marriage.

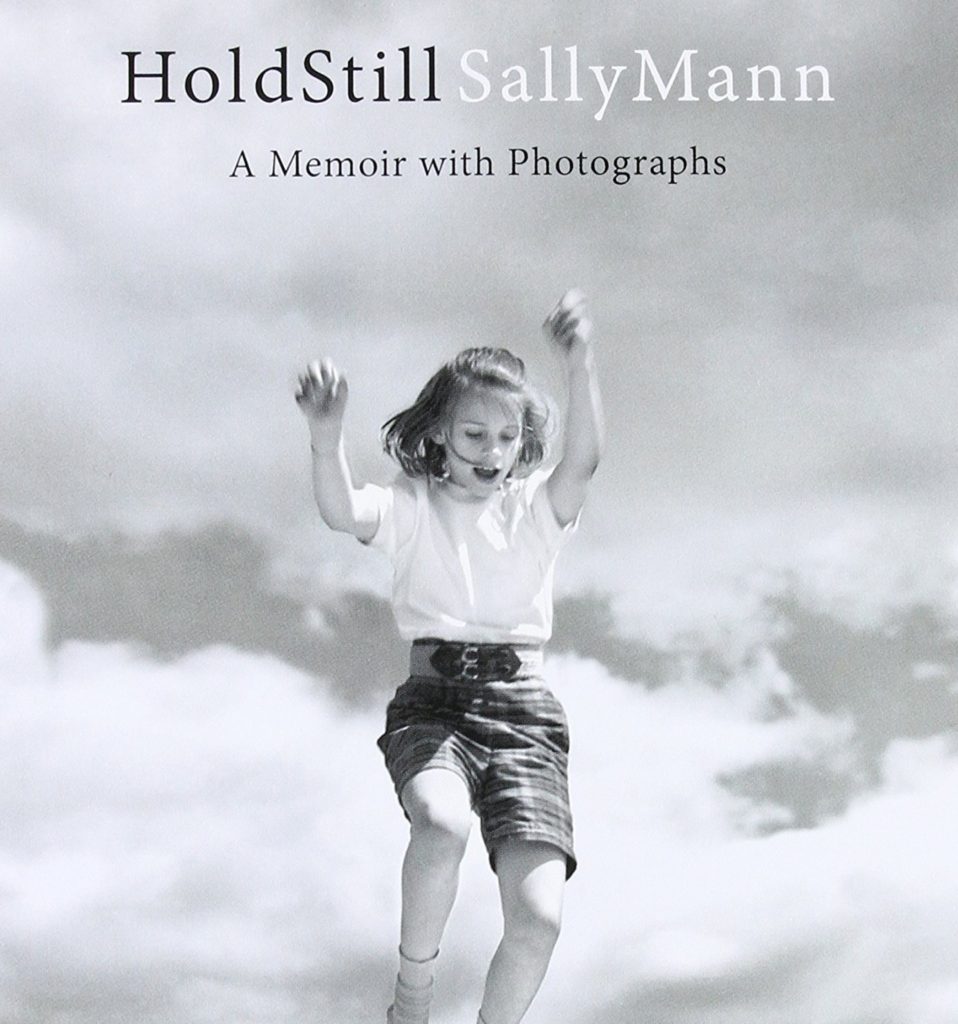

Perhaps that should be unsurprising, given how deeply her psyche and her oeuvre seem to have been marked by the South, its live oaks dripping Spanish moss, its terrible record on race and its multigenerational dynasties hiding gothic Faulknerian secrets.Ī rebellious doctor’s daughter from Lexington, Va., Sally Munger was a Bennington College student when she fell in love with Larry Mann, whose father was also a doctor, but whose parents were fanatical social climbers hoping their Tiffany calling cards might seduce the snooty Connecticut gentry. Now her wonderfully weird and vivid memoir - generously illustrated with family snapshots, her own and other people’s photos, documents and letters - describes a life more dramatic than I had imagined. I’d assumed she was continuing to make new work and enjoying placid rural domesticity periodically interrupted by brief but abrasive trials in the court of public opinion. Before reading “Hold Still,” my knowledge of Sally Mann was based entirely on her photographs of her family on their Virginia farm, her dreamlike Southern landscapes, and some memory of the controversies that have surrounded the question of whether her intimate portraits of her children, often nude, were exploitative.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)